The information provided on this page is available to download as a printable booklet.

Providing personal care to someone living with dementia can sometimes trigger behaviours or feelings that are unexpected. Some of these may be related directly to the brain changes that occur in dementia. Others may be a result of the person’s life history. Often it is a combination of the two. In other words, changes in the brain can lead to the person misinterpreting what is occurring and this leads to memories from the person’s past that trigger distress. Here we describe some of the most frequently reported issues and include some tips to try to overcome these challenges.

This page covers:

- Type and stage of dementia

- Disorientation

- Accusations

- Sleep disturbance at night times

- Sundowning

- Memory and learning

- Memories of personal care from the past

- Disinhibited sexual behaviours

- Communication and language

- Disinhibited talk

- Coordination and practical activity

- Visual perception

- Hallucinations

Type and stage of dementia

There are many different types of dementia. Being diagnosed with the correct subtype can be very helpful in understanding the types of symptoms people experience and the sort of help they may need. Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia are the most common forms. Detailed information about these types can be found on the Alzheimer’s Society website: www.alzheimers.org.uk

Rarer dementias include Frontotemporal dementia, Lewy Body Dementia, Parkinson’s Dementia, Young Onset Alzheimer’s Disease, Posterior Cortical Atrophy, Primary Progressive Aphasia and Familial variants of dementia. Detailed information about these can be found on the Rare Dementia Support website www.raredementiasupport.org

Different types of dementia can also be found in the same brain. This is sometimes referred to as mixed dementia.

Dementia is more prevalent in older age groups. Dementia that is diagnosed under the age of 65 is commonly referred to as Young Onset Dementia. There are particular challenges of living with young onset dementia and in providing personal care. Dementia UK website has some particularly useful information about Young Onset Dementia www.dementiauk.org

Throughout this website we have used the word ‘dementia’ as an umbrella term. Where a particular symptom may be more prevalent in a particular type of dementia we have highlighted this specifically. Everyone experiences dementia differently. Even people with the same type of dementia will not have exactly the same symptoms. Life experiences, other health conditions and general lifestyle will all play their part.

Likewise, one person’s dementia will progress at a different rate to the next. Whilst it might generally be expected that people living with more advanced dementia will need more help with personal care, some individuals will need help with certain aspects of care from quite an early stage. For this reason, we have not specifically used ‘dementia stage’ on this website.

Disorientation

“She has no idea what time it is. She’ll try to get dressed to go out at 11 o’clock at night”

“He gets lost even on the way to the loo”

“When we stay at our daughter’s house, he tries to get into bed with the children”

“They’ll ask when dinner is, even though we ate it 15 minutes ago”

Dementia can cause disorientation on many different levels. People can struggle to know where they are, what time of day it is and who the people are around them.

Imagine how you feel when you wake up on holiday and for a few seconds you cannot work out where you are. That is the feeling of disorientation and for some people living with dementia that feeling may be ever-present. If the person is in a place that is unfamiliar to them, they may lose their way very easily and may feel more anxious about personal care activities.

Top tips for dealing with disorientation

- When in a new environment, walk around a few times and point out important spots, like a picture on the way to the bathroom or which way to turn at the top of the stairs to find the bedroom.

- Post-it notes, labels or pictures on doors and cupboards can also help people to find their way around the environment.

- Try to provide reassurance about safety.

- Provide information about the time of day and place as part of conversation.

- Use familiar items, such as toiletries and clothing, to help the person understand what they need to do.

- Allow the person enough time to adjust to what you need them to do.

- It can be helpful to link personal care to events. For example, “Let me help you with your smart clothes this morning, because we have visitors coming for lunch” or “Let’s get our coats to go to the shops, it’s cold today”.

- People may become muddled over PM and AM on a standard clock face. A digital ‘24 hour’ clock or a special clock face that differentiates night and day may help.

- Add key events, such as visitors, days out and appointments, to a whiteboard or calendar. Ticking off events that have happened may help them to keep track.

- Various smart phone apps can help people keep track of scheduling.

Accusations

“Mum is convinced that the lady who helps with the cleaning is stealing from her”

“He’s accused me of having affairs with practically everyone who comes to the house! Nothing could be further from the truth. After all I do to look after him! How could he even think this?”

“Dad won’t eat anything that the grandchildren make for him to eat. As soon as they leave the room, he says they are trying to poison him”

Sometimes in dementia, people may make accusations that are not based on fact. Examples may include that someone is stealing their possessions, such as a purse, wallet, keys or items of jewellery or clothing; someone is poisoning their food; someone is having an affair with their partner; they’re being spied on, or people are plotting against them. An explanation is that the person is trying to make sense of a changing situation and their declining cognitive abilities mean that they jump to the wrong conclusion.

For example, why should someone they hardly know be spending so much time in their bedroom where they keep all their valuables? Why should so many young men keep calling on their partner and be spending so long whispering in the kitchen?

One theory is that the accused person or the object of the accusation might be a symbol of a loss that the person is noticing. For example, a purse or wallet might represent the realisation that the person is losing their financial independence. The accusation of a partner having an affair with a member of staff from a care agency might symbolise the recognition that their personal relationship is changing, and their partner is becoming a carer rather than a lover.

Accusations, blaming, denying and hoarding often go hand in hand.

Filling a handbag with toilet paper might symbolise a fear of losing continence. Hoarding pens and pencils might symbolise the realisation that writing is becoming more difficult. Collecting keys might represent the fear that they might lose their driving licence or their home. Symbolic items can be so important to the person that they need to be kept safe. The person might hide the item in a safe place, only to forget where they put it. This may result in accusations of theft.

Sometimes it might be difficult to imagine how hard it is for someone to face the reality of their situation.

They may be unwilling or unable to admit that things are changing, and therefore they may be in a state of denial. Accusations and blame may be a way for the person to cope with the awareness that things are not quite as they were.

Of course, it is always important to remember that an accusation may be true. People living with dementia are vulnerable to theft and abuse, so it is important not just to assume that it is the dementia.

Top tips for dealing with accusations

- It is really challenging to be on the receiving end of unfounded accusations.

- Take a deep breath, recognise and then let go of any hurt, frustration and anger that you are feeling. Try to build a bridge into their world.

- The person needs to be heard and listened to.

- Be open to hearing the person’s perspective without reacting, so let them vent.

- Do not argue about the facts or the truth. Do not contradict, try to use logic, or divert their attention. These will only make the situation worse.

- Believe what they are saying.

- Rephrase the accusation as if your best friend was telling you the same thing had happened to them.

- Explore what happened using ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’, ‘how’ and ‘who’, but not ‘why’ questions.

- Notice whether the person is mainly describing what they have seen, heard, smelt or felt. Use their preferred ‘sense’ when asking questions, e.g. if they are describing something they have seen as evidence, then ask them to describe the detail of what they have seen.

- When the person feels heard, they will often feel validated. This helps to diffuse the situation and builds trust and connection. Then it may be possible to restore relationships.

Ways to make accusations less likely to occur longer term

- Over time, as the person realises they are being heard, the accusations may subside.

- It can be helpful to try to work out the meaning behind the accusation. The person may be feeling fear, shame, rejection, hurt, guilt, inadequacy or some other deep emotion and this is the only way they are able to express their feelings.

- A handbag can be symbolic of a person’s independence. It contains cash, cards, mobile phone, diary, contact list, keys and all the important things that a person needs. It is not uncommon for people to hold on tightly to their handbag, not let it out of their sight and to fill it until it’s overflowing with other items.

- Don’t try to remove items that the person holds dear.

- Talk about it with them but let them take the lead on what stays.

- Agree a few safe places where they would like to keep things safe in the home.

Sleep disturbance at night times

“She wakes up in the middle of the night, goes downstairs and tries to start making breakfast at 3am”

“He has terrible nightmares and wakes up shouting”

“When they get up for a pee, they will wander into the spare room and start crashing about trying to find the loo”

Many people with dementia experience poor or disturbed sleep, which can affect their mood or how they manage tasks during the day. Both these factors can have a huge effect on carers, affecting their sleep too. Some types of dementia, such as Lewy Body dementia, can cause frightening hallucinations and nightmares. Sometimes people with dementia may not get much exercise or stimulating activity, so are not physically or mentally tired enough when it is time to go to bed.

Others may take long naps during the daytime which will also affect their ability to go to sleep at night. It is important to identify and treat any physical problems that may interfere with a good night’s sleep, such as arthritic pain, restless legs, constipation or digestive problems. Certain medications for other conditions, such as diabetes or high blood pressure, can also affect sleep.

Get health checked out

- If you are concerned, make an appointment for the person to see their GP. Many GPs do not ask about sleep if a patient with dementia is seeking help about another health problem.

- If the sleep problems are also affecting your own sleep habits, make sure you make the doctor aware of this.

- The GP can assess and treat any general health problems that may be impacting on sleep. Some people think that sleeping tablets might help but these may cause drowsiness or sluggishness on waking, which may put the person at greater risk of falling. Used in the long-term, they can become less effective.

Routines that can help with sleep

- Reflect on the daily routines for the person you support so that they are more likely to sleep when they go to bed. A healthy routine can reduce confusion and help people feel more energetic during the daytime.

- Try to have a familiar, daily routine for meals and activities. This can help the person’s orientation and their body clock. For example, listening to music or a radio programme in the morning or going for a walk or doing some chair exercises after lunch each day.

- If they are able to, encourage the person to help with household tasks, such as preparing vegetables or drying dishes.

- A pleasurable activity such as looking at photographs or other reminiscence aids after the evening meal and before bedtime can be reassuring and reduce anxiety.

- If possible, encourage the person to go outside during the daytime; even half an hour can be beneficial. Daylight helps to set the body clock and encourages the person to feel sleepy when it goes dark. If the person can’t get outside easily, a bright daylight lamp indoors can have a similar effect.

- Discourage the person from napping for long periods during the day.

- Setting a routine for going to bed is important. A warm milky drink, using the toilet, having a wash and cleaning teeth in the same order each evening, perhaps with some relaxing music once in bed, can be helpful ways of establishing routines.

- Some people enjoy being read to. Favourite poems or short stories or listening to the radio helps some people drift off.

- You may consider reducing caffeine in the afternoon and evening as this is a stimulant that can keep the person awake and may make them want to go to the toilet in the night. Decaffeinated alternatives may be a good option to try. Alcohol and nicotine can also disrupt sleep.

Technology and changes at home to help sleep

- Keep the bedroom free of clutter and as quiet and dark as possible. A nightlight might help the person find the bathroom in the night or reassure them if they get anxious in the dark.

- If the person is regularly getting up during the night you might consider some technological aids, either to alert you that they are up and about or to make the environment safer and reduce the risks of falls.

- There are sensors that will turn on the light when someone gets out of bed, so that they can see their way to the bathroom.

- A social worker or an occupational therapist can advise on what technology might be suitable and what they are willing to provide.

Sundowning

“He’s fine all day, but gets ever so upset when it starts to get dark”

“Around tea -time, my sister starts to worry about our Mum who has been dead for many years”

Sundowning refers to a pattern of increased confusion, restlessness, and agitation that typically occurs in the late afternoon or early evening. The changes in natural light and the approaching darkness can contribute to this.

It may trigger familiar patterns of activity such as collecting children from school or leaving work to get home. It may be that the person becomes distressed wanting to ‘go home’ when they already are or may be looking for someone that is no longer there. If personal care needs to be done at this time of the day, it is important to be aware that this is a factor to consider.

Top tips for dealing with sundowning

- Speak calmly and reassuringly. Do your best to understand what the agitation is about.

- Giving reassurance by acknowledging feelings and exploring feelings. For example, “I know you want to go home, what is it you want to do when you get there?”

- When a person is agitated or stressed, it’s always a good idea to check for other underlying causes such as tiredness, hunger, thirst, pain or feeling insecure or unsafe.

- Lower natural light at the end of the day may impact on the person’s ability to make sense of their surroundings.

- Lower light levels can also trigger problems with visual processing or hallucinations.

- Before sundowning symptoms start, is it possible to do something that either helps to calm agitation or increase relaxation and help the person to understand the environment that they are currently in?

- Other helpful strategies include making the environment cosier, closing curtains, making sure that lights are not creating shadows, ensuring the room is warm and turning off any unpleasant background noises.

- Use additional lighting and soothing, calm activities.

Seek support from healthcare professionals and local dementia services if the problem is persistent or get advice from the helplines Alzheimer’s Society 03331 503456; Alzheimer Scotland 0808 8083000; Dementia UK 0800 888 6678; Dementia Carers Count 0800 652 1102.

Memory and learning

“There’s nothing wrong with their memory! They remember things from our childhood that I’ve completely forgotten about”

“He remembers when he wants to!”

“I’ll show him how to do something and five minutes later he’ll deny I’ve ever shown him!”

“Why does she ask me the same thing over and over again?”

Making new memories is often affected in dementia and particularly in Alzheimer’s type dementia. Generally, memories that were made before the Alzheimer’s took hold will be better preserved than memories from the more recent past. Remembering the names of recent grandchildren may be more problematic that remembering the names of brothers and sisters. Memories that are well stored in the brain can be remembered.

Learning new information and then getting this into longer term storage is often more of a problem. This does not mean that people cannot learn new things, but it may take longer for them to be laid down in the memory store in a reliable way.

Top tips for supporting someone with memory problems

- Conversation topics that draw on the person’s past passions and interests are likely to be easier than ones that concentrate on events in the past week.

- Conversations about current feelings and the here and now will be easier too, as these don’t require memory at all. For example, “Are you feeling hungry?” or “Do you like the food you are eating?” will be easier than “When did you have dinner, what did you eat?”

- Having objects that evoke memories of the past can make conversations easier.

- There may be objects such as particular toiletries, soaps, towels that people find easier to use and will make personal care more enjoyable for them.

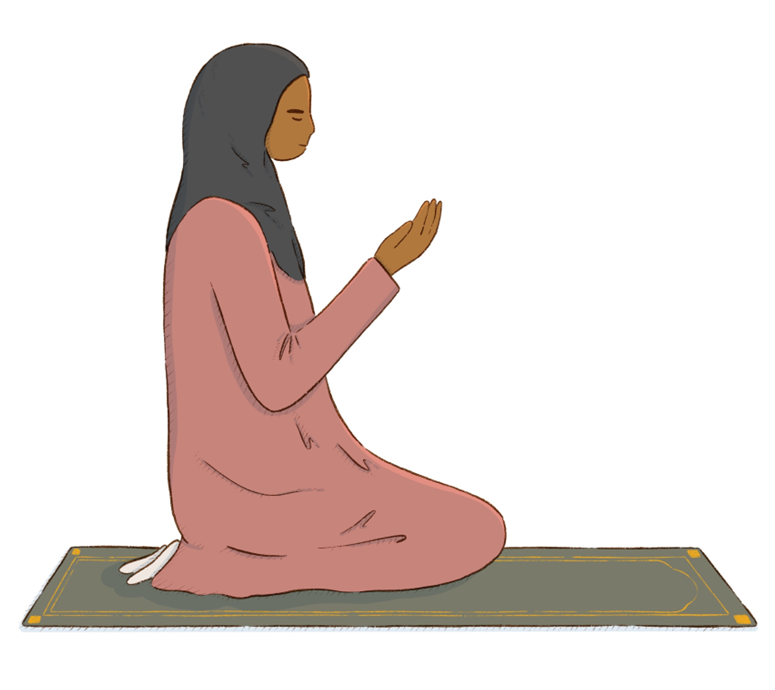

- Items such as prayer mats, beads, images relating to their faith may help trigger faith and belief memories.

- Songs from the person’s past may be remembered in detail and singing songs together can sometimes help people enjoy care activities.

- People with dementia can often learn new things, but they will need repeated practice.

- Repeated practice is easiest to learn if you keep the words used and routines the same each time. This can be especially helpful when thinking about someone’s personal care routine.

- The person may not remember that they have asked a question before or that you have just shown them something. This is a symptom of poor new learning in dementia. The person will rarely do this deliberately.

- Think about someone’s morning routine, do they brush their teeth first when they wake up? Do they like to shower before eating breakfast or after? Try to encourage prompts with their personal routine in mind.

- New routines and habits will be learnt. They just take more time to sink in.

Memories of personal care from the past

“She often calls me mum when I am helping her to wash”

“They’ll ask me for a kiss goodnight when I’m putting them to bed!”

“Sometimes, when I’m helping him use the loo, he will get very upset and push me away”

“She goes rigid when I am trying to get her undressed and into her nightie. I don’t know what to do?”

Our main experiences of being helped with personal care often come from our childhood. Other people may have experienced help with personal care as adults because of illness or disability.

Some people have had happier childhoods than others and some care experiences may have been better than others. Many memories that we have of past experiences are buried deep within our minds, but these can be triggered when we find ourselves being helped with personal activities.

Top tips for helping someone who mixes up past and present

- It is quite common for people who are being helped to think that their ‘helper’ is actually a parent figure. The person you are caring for may call you mum when in fact you are a granddaughter. This can be quite a shock, but try not to overreact if this happens. Continue with the conversation.

- At other points in people’s lives, they may have received personal care linked to health issues and may find memories of these times of vulnerability coming back. They may talk about them or interpret the way things happen now based on what they learnt then.

- It’s always helpful to explain clearly what you would like the person to do or what you will help them with, step by step, so they can be as involved as possible and receive help in a way that makes sense to them and helps them feel comfortable.

Distressed reactions linked to past memories

- If the person you’re supporting finds it difficult to separate the help you’re wanting to provide now from events in the past and they seem distressed, consider whether you need to continue at this point or whether you can try again a little later.

- Older, LGBTQ+ and other minoritised individuals with dementia may have experienced discrimination and abuse, including from those in power such as the police. Trauma may resurface especially when dealing with those in uniforms such as ambulance personnel. This can trigger memories.

Get some help

- Sometimes, if a person has suffered abuse during personal care type activities during childhood or adult life, or has had some very traumatic experiences, it may trigger emotional reactions. Having some advice from your doctor or mental health professionals might help to make a plan for how to provide care that causes as little distress as possible.

- If the reaction is extreme and occurs on a regular basis then you will need to seek professional help through your GP or community mental health team.

- It may be that an outside agency may be better placed to provide personal care in this situation.

Phone any of these helplines: Alzheimer’s Society 03331 503456; Alzheimer Scotland 0808 8083000; Dementia UK 0800 888 6678; Dementia Carers Count 0800 652 1102. Nothing that you discuss will shock or embarrass people on the other end of the phone.

Disinhibited sexual behaviours

“Honestly, some of the things they do when I’m trying to wash them make me so embarrassed”.

“I don’t know where to look sometimes when I’m changing her.”

“I get so embarrassed when people tell me what he’s done and said to them.”

“He used to be such a private person, now it’s like he has no boundaries.”

Sometimes within dementia, people may lose the ability to control strong urges or seem to be unaware of the right time and place for some behaviours.

This can sometimes be the case particularly if a person has a dementia that affects the front part of the brain. In some instances, this can lead to inappropriate sexual touching of the carer or masturbation, particularly when being given personal care.

Inappropriate touching is very distressing to be on the receiving end of.

Many people who masturbate are seeking comfort in their own bodies. For some it helps them to get to sleep at night. For others it’s the pleasure they can experience where they are in control of their own body. It is often a very uncomfortable thing to witness for family carers since masturbation, although natural, is something that usually occurs privately. The time and place may be the issue. Knowing when the person might be likely to masturbate will help you to support them to be in a private space, and enable you to give them time alone to do what they need to.

Top tips for dealing with disinhibited sexual behaviours

- If you know that the person has disinhibited behaviour, try not to react angrily.

- Initially, voicing your concern at the behaviour such as “I find it upsetting when you do that” may help the person to realise they have caused offense.

- Sometimes, if you know the person well, humour can help to diffuse the situation. However, sometimes this may just inflame the situation further.

- In these instances, it can help to steer the conversation onto a different topic.

- If the situation is escalating worsening or becoming difficult to manage then finish what you are doing and if possible remove yourself from the situation. Reach out for help if you need to.

Think about what you can do differently in the future

- Reflect on whether there was something specific that appeared to trigger the sexual response and if possible, plan to take a different approach in the future.

- Think about whether this happens at particular times of the day and try to alter the pattern of personal care to accommodate this.

- If the person is touching themselves or masturbating, then provide them with privacy to do so.

Get some help

- Being subject to this sort of experience is upsetting and it is important to talk to someone supportive about this after it has happened.

- If this is a persistent problem, then talking to your GP or community mental health team or Admiral Nurse team is recommended.

- It may be that an outside agency may be better placed to provide personal care in this situation.

- Remember that it is important to ask for help.

Phone any of these helplines Alzheimer’s Society 03331 503456; Alzheimer Scotland 0808 8083000; Dementia UK 0800 888 6678; Dementia Carers Count 0800 652 1102. Nothing that you discuss will shock or embarrass people on the other end of the phone.

Communication and language

“Why can’t she follow my instructions?”

Why can’t he tell me what he needs me to do?”

“Whatever I say, they seem to get the wrong end of the stick?”

“Why is conversation so difficult?”

“Why has she started speaking in a foreign language?”

“Why does he use such coarse language? I’d never heard dad swear before he got dementia.”

Dementia often affects parts of the brain that are concerned with speech and understanding what is being said. This is sometimes referred to as expressive and receptive dysphasia. This does not mean that the person stops wanting to communicate and to understand what is going on. Feelings remain as strong as ever. The person will often be alert to picking up on anger, even if they do not fully understand words and sentences.

Communicating well during personal care can make a lot of difference to how smoothly things go. You can’t fix the situation, but you can try to see things from the person’s perspective to try to understand their reality. By using their reality as a starting point, conversation can become easier. The section on disinhibited talk may also be of interest.

Top tips for tuning into the person’s feelings

- Even if someone speaks very little, always assume that they can understand what is being said in front of them.

- Try to step into the person’s shoes to identify how the person is feeling.

- Be sensitive to what the person is communicating to you, both the words they use and in their body language.

- Try not to point out mistakes, or the person may feel criticised and lose confidence.

Top tips for getting a conversation going

- Face the person you are speaking with.

- If they are seated, drop down to their level.

- Communicate your willingness to be helpful.

- Speak in a way that is reassuring.

- Make sure your body language matches your words.

- Use adult language and voice tone that is very respectful.

- Use open questions such as “How are you feeling today?”

- If the person finds it difficult to find the word to answer then using closed questions such as “Is that painful?” or “Do you feel comfortable?” may make it easier for them to respond.

- Try to tune into how the person is feeling. Is the person happy or unhappy? Relaxed or tense? Calm or angry?

- If you recognise the emotion then say that you recognise it, e.g. “You sound excited/scared/happy/sad/worried/angry”.

- Try to find a topic of conversation that you know interests the person you are helping. The earlier section on memory and learning may help with this.

Top tips for helping the person follow what you need them to do

- Give them your full attention – avoid checking your phone or doing another task at the same time.

- Sometimes giving people a choice of two things, such as “Do you want the blue shirt or the red shirt?” may get a better response than saying “What shirt would you like to wear?”

- Showing people a selection of shirts may help them make a choice by pointing.

- Too much questioning can cause distress. Try to work on one topic at a time.

- Many people with dementia will have the ability to read, but may need text in a larger font. Having a selection of single words or phrases and a descriptive picture can help in different situations with communication.

- Technology can sometimes help with communication difficulties such as Talking Mats. You can find out more about the use of Talking Mats by visiting their website www.talkingmats.com

Top tips for people who have a different first language than their carer

- People who speak two or more languages may increasingly speak in their first language (sometimes called mother tongue) as dementia progresses.

- People may often lose their ability to speak a second language much more quickly than their mother tongue.

- This is the case even when people have been fluent in a second language.

- If this happens, it is important to provide opportunities for people to converse in their first language. This will usually make the person feel more at ease and be able to explain concerns more easily.

- Learning key phrases in the person’s first language can help make communication easier.

- Many people with dementia will have the ability to read, but may need text in a larger font. Having a selection of single words or phrases in the person’s first language alongside a descriptive picture can help in different personal care situations.

Swearing

As dementia progresses, general communication is often impaired. For some people, however, language which expresses high emotion such as swear words remains intact. Swear words, that the person may not have used prior to their dementia, may be used more frequently. This can often occur during personal care activities.

Swearing can sometimes be a defence mechanism reflecting that the person is feeling challenged or rushed.

Top tips for dealing with swearing

- It can be really challenging to be on the receiving end of swearing when you are trying to help someone.

- Take a deep breath, recognise and then let go of any hurt, frustration and anger that you are feeling.

- Recognise that this is usually a symptom of the dementia and not deliberately done to cause offence.

- Having a swear can be a useful way of letting off steam for some people.

- Try not to react directly to the swear words. Listen to the emotions behind the language and deal with that.

- Explain to new people or family and friends that the swearing will occur but that it is part of the dementia rather than deliberately meant.

The following section on disinhibited talk may also be useful.

Disinhibited talk

“Why is he so rude?”

“Some of the things she says to me are really hurtful! I’m only trying to help!”

“He used to be so polite. Now he seems to go out of his way to cause offence!”

“I get really embarrassed by some of the things they suggest”

Sometimes in dementia, people lose the ability to stop themselves saying things out loud that go through their mind. This is often a result of damage to the front part of the brain. This may cause the person to make hurtful comments about someone’s appearance or make racist or sexist comments. Saying these things may seem completely out of character and this change can feel quite shocking. This is a sensitive area of communication.

Top tips for dealing with disinhibited talk

- If you know that the person can speak in a disinhibited way, try not to react angrily and let others who provide care know that it might happen.

- Initially, voicing your concern at the comment such as “I find it upsetting when you say that” may help the person to realise they have said something offensive.

- Sometimes, if you know the person well, humour can help to diffuse the situation.

- However, sometimes this may just inflame the situation further, so it’s important to use your judgement here.

- In these instances, it can help to steer the conversation onto a different topic.

- If the situation is worsening and becoming difficult to manage, then finish what you are doing and if possible remove yourself from the situation.

- Being subject to verbal abuse is upsetting and it is important to talk to someone supportive about this after it has happened.

Phone any of these helplines: Alzheimer’s Society 03331 503456; Alzheimer Scotland 0808 8083000; Dementia UK 0800 888 6678; Dementia Carers Count 0800 652 1102. Nothing that you discuss will shock or embarrass people on the other end of the phone.

If this is a persistent problem, then talking to your GP or community mental health team or Admiral Nursing team is recommended.

Coordination and practical activity

“Why is he so clumsy?”

“Why does she do the exact opposite of what ever I say?”

“I know she can do more than she lets on!”

“Sometimes I think they’re just being awkward?”

“Why does he make such a mess of things?”

People with dementia can have damage to the part of their brain that is to do with coordination during practical activities. This is sometimes called dyspraxia or apraxia. This impacts on the ability of the person to use their hands and body in tasks like eating, food and drink preparation, dressing and washing. The person’s limbs can be working perfectly well but the overall control and coordination can be the problem.

If this is not understood, it could be misinterpreted that the person is being awkward or thoughtless. An example of this may be when someone is trying to put a shirt on and they can’t work out how to put their hands down the sleeve. This problem often gets worse when we try to help with instructions about how to do it correctly.

These sorts of problems can be helped by a specialist assessment from an occupational therapist (OT) or a cognitive rehabilitation specialist.

The earlier section on visual perception may also be useful.

Top tips for helping with personal care if the person has coordination problems

- Does the person have difficulty in hearing or understanding the request or instruction?

- Check hearing aids, glasses.

- Reduce distractions such as background noise from the TV.

- Make sure you are communicating well.

- Does the person have difficulty in planning how to do the task?

- Break the request or instruction into single steps. For example, rather than saying “Now wash your face” you might say “Pick up the flannel first”.

- Sometimes, singing a favourite song with a person whilst you are helping them dress means that they may put their arms in the shirt automatically rather than being muddled by instructions.

- Does the person appear to not know how to start a task or become overwhelmed once they get started?

- Start the activity yourself, to prompt the person to get started. For example, turn the tap on so that the water is running.

- Name objects when you give them to the person. For example, “Here is your hair comb”.

- Pat the person’s body part as you ask them to move. For example, tap their arm as you say “Push your arm into the sleeve”.

- Does the person have difficulty identifying what is happening?

- Use a running commentary to explain what you are doing as you do it, e.g. “I am just lifting your foot now to help you get you slipper on”.

Visual perception

“Sometimes I think they’re going blind!”

“He’ll stare at his cutlery like he’s never seen them before”

“He lifts up the cushion on the chair and tries to have a wee there!”

“She deliberately puts herself on the floor next to the chair”

“He’s always bumping into things”

We use our eyes to see but it is our brain that makes sense of colours and shapes, to interpret the world visually. Some dementias impact on the person’s ability to see the world in the way that others see it. Sometimes this leads to people not being able to recognise everyday objects such as hairbrushes or cutlery. This is sometimes referred to as Visual Agnosia.

This is made worse when objects don’t look like they do in our minds eye. For example, think about the toilet flush that you used in your teens and compare that with the wide variety of toilet flush now. Objects that look like each other, such as toilets, bins and handbasins can be confusing. If someone needs to use them quickly, this confusion can lead to difficult situations. It may result in the person trying to use a handbasin or bin as a toilet.

The section on hallucinations may also be useful.

Top tips for supporting someone with visual perception problems

- If a person gets objects muddled, try to ensure that the objects you use in personal care have a familiar look to them.

- Providing verbal prompts about the object being used or putting the object in the person’s hand, whilst providing the verbal cue can also help. For example, putting a hairbrush in the person’s hand and saying “Here’s the hairbrush that you like to brush your hair with” may help the person to recognise what is expected for them to do next.

- You can help the person to identify an object by asking them to physically feel the object and tell you what they feel. This means they use other pathways in the brain rather than just visual ones.

- Sometimes, people cannot identify an object from the surrounding objects or a cluttered background. Ensuring that objects in the bathroom look different from each other can help here, for example using a dark coloured toilet seat or a brightly coloured bin rather than having everything in white porcelain.

- A person with this problem may also have difficulties finding a particular object from the cupboard, selecting a garment from the wardrobe or picking up a knife, fork, or spoon from the drawer if they are all put together.

- It is helpful to declutter these types of spaces and leave only those objects needed for the task at hand in eyeshot.

- Placing the object on a contrasting background may help. A white plate on a white tablecloth with mostly white food could be difficult for someone to see. Think about providing a coloured plate to create contrast between the food and table.

- Some people with dementia have difficulty being aware of the space between their body and objects. For example, they might stand too close to a table or a door. This can mean that a person may frequently bump into things.

- They may feel anxious when using the staircase. They may mix up the directions in different dressing tasks (e.g. front and back, right and left, inside out) and find it difficult to grasp an object when reaching out for it.

- Visual perceptual problems will be made worse if the person has not got the correct glasses prescription or their glasses are dirty or scratched.

- Good lighting is important for visual perception. Try to make sure there are no shadows that could be misinterpreted as objects.

Hallucinations

“She insists that there is a man standing behind the door in the bedroom when I’m helping her get dressed”

“Sometimes they’ll say there is a cat sitting by the chair when I’m helping them eat dinner. It freaks me out a bit”

Hallucinations can occur for many reasons. Most commonly in dementia people will experience visual hallucinations (seeing things that are not there) and sometimes people may hear things that aren’t there (auditory hallucinations). Generally, this will be due to the brain misinterpreting sights and sounds as something else.

Visual perception sometimes becomes disturbed in dementia because of the damage to parts of the brain that help people interpret the visual world. This is particularly prevalent in Lewy Body dementia or Parkinson’s Dementia. Sometimes people will report seeing people or animals that cannot be seen by others. These experiences can be confusing and troublesome. They may occur as part of personal care activities.

Top tips for dealing with hallucinations

- Don’t dismiss these ‘hallucinations’. They are very real for the person experiencing them.

- The person needs to be heard and listened to.

- Say that you cannot see what the person is seeing but you believe they can see them.

- Sometimes it helps to explore why the person is seeing or hearing something different to you. What meaning do they give the hallucination?

- Provide reassurance that the hallucination is not going to harm them. Work with the individual’s reality rather than making judgements.

- Sometimes saying that maybe their eyes or ears are playing tricks can help.

- When the person feels heard, they will often feel understood. This helps to diffuse the situation and builds trust and connection.

Top tips for decreasing the likelihood of hallucinations in the future

- Reflect on what appears to have triggered the hallucination and alter the care activity routine to accommodate this.

- Sometimes the hallucinations occur when someone’s brain misinterprets what it can see. Shadows, or the outlines of objects, can look like a person or an animal.

- Try to alter lighting to see if this helps, for example with sundowning.

- Move objects away (e.g. a dressing gown on a bedroom door might look like a person) or cover them up if you think they might be misinterpreted.

- Try playing music at the time when they usually hear things, to see if that helps with auditory hallucinations.

- Sometimes people can experience hallucinatory type experiences if they have an infection or as a side effect of medication. This can be reversed once the infection or the medication issue is rectified. If you are concerned, you should consult a health professional.