The information provided on this page is available to download as a printable booklet.

Over time, dementia can impact on the person’s ability to make decisions and informed choices. There are a number of good practice and legal processes and guidelines that can help with this.

Here we describe those that you may most commonly encounter and how these can be used.

“He can’t make decisions anymore. Where do I stand legally?”

“Mum needs the carers but she sends them away all the time! What can I do?”

This page covers:

- Mental capacity

- Lasting Powers of Attorney (LPA)

- Advanced Care Planning (Advance Statements)

- Advance Decisions and Advance Directives (Living Will)

- Attendance Allowance

Mental capacity

“She has dementia. Of course she can’t make decisions!”

“He will give all his money away to anyone with a sob story. How can I protect him?”

Dementia in itself does not mean that people no longer have capacity to make decisions. People are still able to make their preferences known about personal care even in advanced dementia.

Decisions and choices that are made in the here and now about what to eat or when to wash are relatively straightforward for people. As a carer you may not always agree with these preferences but the person’s decisions should be respected unless there is good reason not to.

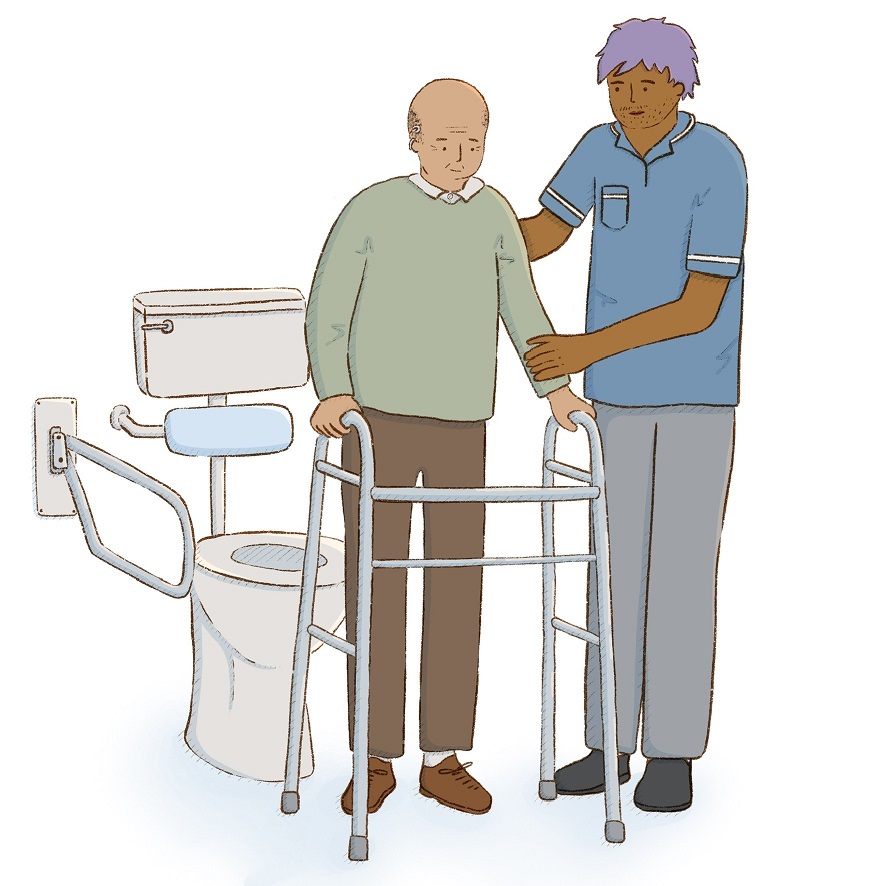

When supporting someone living with dementia with personal care, there may be times when the person refuses care that a carer feels is in their best interest. A typical example would be not taking medication or giving money away.

Some decisions are much more difficult to make than others. Some decisions have big consequences for health and wellbeing that the person may not recognise. People with dementia can be vulnerable to abuse so it is very important that there are laws that deal with people who, because of an illness such as dementia, cannot make a decision themselves.

In England and Wales this is governed by the Mental Capacity Act 2005. In Scotland this is the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. In Northern Ireland it is the Mental Capacity Act NI (2016). This legislation is underpinned by similar principles to safeguard the welfare, property and finances of people who are vulnerable including those with a diagnosis of dementia.

Under these laws, it is assumed that the a person has the capacity to make a decision themselves unless proved otherwise. Capacity is linked to a specific decision. A person may be able to make decisions about taking medicine but may lack capacity about how to spend their money. Capacity to make specific decisions can change over time.

- Wherever possible, help people to make their own decisions.

- Do not treat a person as lacking the capacity to make a decision just because you think their decision is unwise.

If you are trying to decide what is in the person’s ‘best interests’ then you need to consider:

- What they would have wished to have happened before their dementia? The person’s values, beliefs and preferences will be important here.

- What does the person themselves and others who know them well say about the decision?

If you think that the person is making a decision that is not in their best interests, then a health or social care professional can carry out a Mental Capacity Assessment. This will be with regards to a particular issue at this point in time. They will assess whether the person can understand the decision and retain that information so they can weigh up the pros and cons and can then communicate their decision. If the trained professional judges that the person does not have capacity then a decision can be made as to what is in that ‘person’s best interests’. This is most straightforward if as a carer you have Lasting Power of Attorney.

Lasting Powers of Attorney (LPA)

“Is it legal for me to make decisions for the person I am caring for?”

In English law there is no assumption that spouses/civil partners/next of kin can make a decision for someone with a diagnosis of dementia. In the absence of an LPA then spouses/civil partners/next of kin are often consulted about decisions, but not always.

If an individual is not married or in a civil partnership with a long term partner, however, it becomes even more important to consider LPA.

Granting someone to have Lasting Powers of Attorney over your affairs grants them specific rights within the Mental Capacity Act 2005. The relevant legislation in Scotland is the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. English LPA’s can be used in Scotland, but they need to be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian for Scotland. Likewise, Scottish Power of Attorney can be used in England.

In England and Wales there are 2 types of LPA and different people can be appointed to the two different roles.

LPA for property and financial affairs can be used whilst the person still has capacity with the person’s permission so that their finances can be managed in their best interests.

LPA for health and welfare only comes into operation if the person is deemed to have lost mental capacity and the person can then make these sort of decisions. These are particularly pertinent to personal care.

- LPA’s of both types can be made and registered online at www.gov.uk/power-of-attorney

- As it is a legal document that must be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian, many people choose to do this through a solicitor.

- The person granting LPA must have Mental Capacity to understand what they are committing to at the time of the application.

In Scotland, the split between Financial and Welfare Power of Attorney is broadly the same, but different language is used.

- Property & Finance LPA is called a Continuing Power of Attorney. Health & Welfare LPA is called Welfare Power of Attorney.

- The age limit for an attorney is lower in Scotland, at 16 years old.

- In Scotland, if no Power of Attorney is in place and an individual loses capacity then a court will appoint a ‘Guardian’ (Deputy in England & Wales). There is also the option for a one-off ‘Intervention Order’. You can find more information on www.publicguardian-scotland.gov.uk

In Northern Ireland, information about Enduring Power of Attorney can be found on the NI Direct Government Services website www.nidirect.gov.uk

Advanced Care Planning (Advance Statements)

“It’s still early days since the diagnosis but I worry about the future. What can I do to prepare?”

“How can I know what they will want as the dementia advances?”

Advance Care Planning (ACP) is a process that involves conversations about wishes and preferences for care in the future. They are sometimes also referred to as Advance Statements particularly in Scotland. They are not legally binding, but they help carers to understand and respect the views of a person with dementia if there comes a time when the person can no longer communicate about the kind of help they want.

Some people think an ACP only relates to wishes and preferences for end of life care. However, an ACP can also be about how the person would like to be supported with their personal care. Advance care planning has been noted to be particularly important in LGBTQ+ support to ensure that the person’s wishes about care being delivered in a gender affirming way and that all aspects of an individual’s identity, wants and wishes and are considered and respected.

Top tips about Advance Care Plans/Statements

- It is the fine details that vary from person to person. Make sure these are in the advance care plan along with other important wishes and preferences.

- Talk over time to the person about what would be important for you both if you had to provide guidance on how personal care was to be delivered. Highlighting the different preferences between you can help you make sure you really understand the other person’s point of view.

- Providing information about things that are important to the person such as choice of toiletries, process of cleaning teeth before or after eating, face washing, washing after going to the toilet, preference for bath or shower etc. can make a big difference to how smoothly activities can be accomplished.

- These conversations can take place over many months. Record these discussions (either on paper or electronically) so that you have it all to hand when the time comes.

- You can find some templates that could be helpful provided on a number of websites including www.dementiauk.org

Advance Decisions and Advance Directives (Living Will)

“There is a lot of talk about end of life decisions. How do people with dementia make sure that their wishes are respected when they may not be able to say for themselves what they want?”

Advance Decisions are legally binding and specifically relates to the person’s decisions about refusing life sustaining treatments in the future. In Scotland, these are referred to as Advanced Directives and although they are not legally binding, they are still widely recognised and commonly used to guide end of life practices. They are written at a time when the person has the mental capacity to make such decisions.

It can be surprisingly difficult to have a discussion about these issues. If you are supporting someone living with dementia, you may well be asked in the future about their wishes. If you have had the discussion – and particularly if it is recorded in a document – you will feel much more confident that you are acting in the person’s best interest.

Top tips about Advance Decisions/Directives

- Some of the resources below may help you in getting started:

- Video conversation about having difficult conversations can be found on www.mariecurie.org.uk

- Written information about starting conversations and a checklist that may be helpful for families can be found on www.myfarewelling.com

- Search www.hospiceuk.org for the Dying Matters Resources for talking about dying.

- Good Life, Good Death, Good Grief has written and video resources explaining what happens when someone dies, signs to be aware of, ways to have conversations, practical considerations which can be found here www.goodlifedeathgrief.org.uk

- If they are to be legally binding, Advanced Directives must comply with various rules and regulations.

- The charity Compassion on Dying provides guidance for completing this online www.compassionindying.org.uk

- Many people choose to do this through a solicitor to ensure legal compliance.

Attendance Allowance

“Is there funding to help with personal care?”

If a person needs regular help with personal care they will almost certainly qualify for Attendance Allowance. Once someone has reached state pension age, and they have a physical and/or mental disability, and need help to go about their daily routine, they are entitled to money each week to support this. This is called Attendance Allowance. It is important to note that this allowance is not means tested. Those who are entitled to it, regardless of their financial situation, can get it.

In England and Wales

- There are two different tiers of financial support. The lower one is for where help is needed in the day or the night. The higher one covers where help is needed in the day and in the night

- Information can be found via the Attendance Allowance claim form on www.gov.uk. There is a helpline number on 0800 731 0122.

- You will need to fill in a lengthy form that you can either download or it will be sent to you. Ask for help filling it in if you need. Age UK ageuk.org.uk and Citizens Advice www.citizensadvice.org.uk can help.

- When applying for Attendance Allowance, ensure you are honest with the support needed. Stating that the person can do things that they cannot, will result in the person not being awarded the allowance.

- It is worthwhile requesting a Social Work Carers Needs Assessment.

In Northern Ireland

Information about Attendance Allowance can be found on the NI Direct Government Services website www.nidirect.gov.uk

In Scotland

Attendance Allowance and PIPs are being replaced by Disability Payments. Search the Gov Scotland website for more information www.gov.scot and www.homecare.co.uk

Any adult in Scotland who the local authority has assessed as having personal care needs, is entitled to free personal care. This includes under 65’s, so it is relevant for people with Young Onset Dementia.

Young onset dementia is likely to be funded through self-directed support, rather than attendance allowance. Find out more info by visiting the ‘Free personal and nursing care: questions and answers’ page on the Gov Scot website www.gov.scot